- Destinations

- Experiences

- Stay

- What's new

- Celebrating People

- Responsible Tourism

- CampaignsCampaigns

- Subscribe

- Buy Now

On my way back from a trek in upper Kumaon in early April, I came up against the first of the forest fires that were sweeping through the lower foothills. While approaching Binsar, I was confronted with a heartbreaking sight. The smoke from a nearby fire hung in the air of the high ridge on which stands Binsar&rsquos forest. The atmosphere was unnaturally hot. Suddenly, a small animal jumped out in front of our vehicle and dashed to the other side. We slowed down and I looked back to see a beautiful red fox, panting, looking confusedly at the direction of the forest that he&rsquod come from and then staring at the cultivated fields further down the valley. For a wild animal, the poor choice was to either burn in the fire, or take his chance with human habitation.

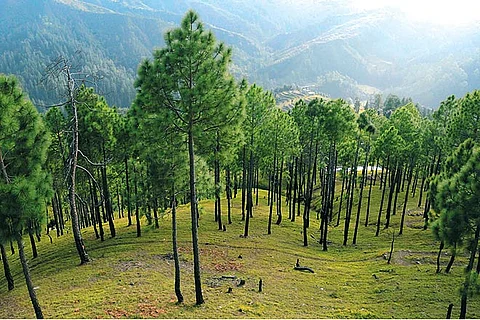

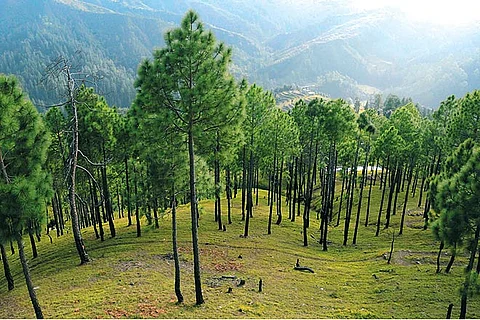

At the heart of these fires lies that detestable tree the chir pine. First planted in the Western Himalaya under the confused mandate of the nascent Indian Forestry Service as a commercially useful timber, this species has run riot, replacing native Himalayan broadleaf trees like oaks. Although these were supposed to be harvested, they were allowed to remain and, today, these aggres­sive trees threaten to oust all other kinds of old-growth forests. Unlike broadleaf trees that ensure that rainwater percolates to the soil, thus recharging the groundwater of the mountainside, the greedy chir sucks it all up. It then sheds its needles which cover the immediate area and prevent any underbrush from sprouting. Chir pine resin and the trees themselves are tinder-dry, perfect for the spread of fires. However, once the fires destroy the broadleaf forests, the chir, due to the fact that it can grow on poor soil, makes a quick comeback and spreads higher. And so the inexo­rable march of the chir pine continues, drying out entire moun­tainsides, obliterating natural springs, loosening rocks. And yet, the government plants more of these, and calls it &lsquore-forestation&rsquo