- Destinations

- Experiences

- Stay

- What's new

- Editor’s Picks

- Responsible Tourism

- CampaignsCampaigns

- Subscribe

Many communities like the Rajputs and the Bishnois keep camels in Rajasthan, but one caste in particular is famous for its close relationship with the animals the Raika.

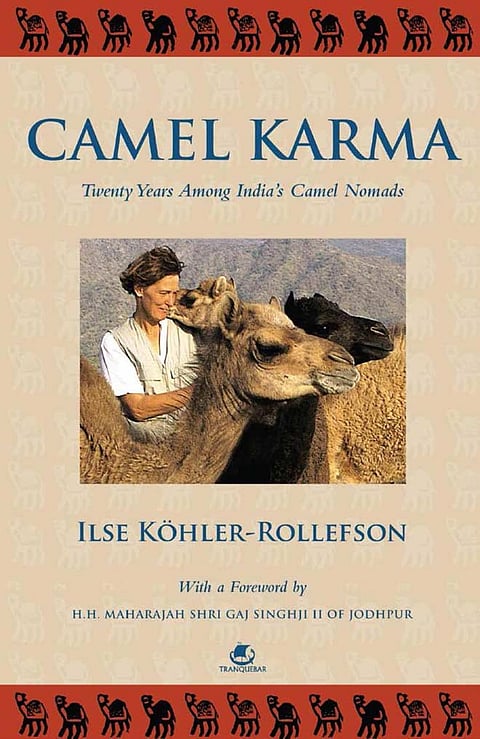

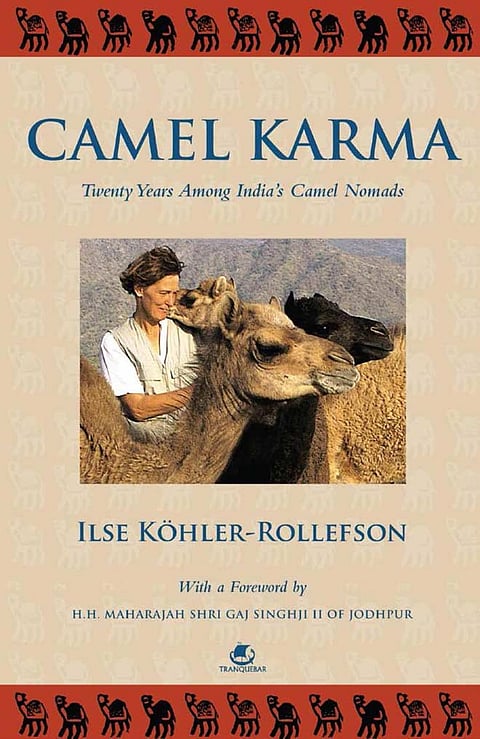

Ilse Köhler-Rollefson, a German veterinarian and zooarchaeologist, came to Rajasthan in 1990 to study the unique camel rearing traditions of the Raika. In the course of research for a PhD, she discovered that camels were doing poorly. Being a pastoral community, the Raika don&rsquot own land and depend on fallow fields, village commons, and forests to find forage for their herds.

Farmers intensified farming by sinking tubewells, and fields didn&rsquot lie fallow for long. The state appropriated village commons in some parts to set up solar and wind farms. The Forest Department forbade livestock from forests and penalised trespassers. The Raika were fenced out of their traditional grazing grounds, and the health of their herds suffered. Epidemics such as trypnosomiasis decimated camels, and the Raika shifted to sheep and buffaloes. Worse, some sold their female camels for meat, traditionally considered a taboo.

In travel journal style, Camel Karma chronicles these upheavals in Raika society and livelihoods. With the increasing marginalisation of camel rearing, Köhler-Rollefson set up the League of Pastoral Peoples to champion the cause of pastoral rights globally. She traces the astonishing transformation of another person in the book. Hanwant Singh Rathore, a taxi driver who drove her across the state during her research, became her partner in an Indian NGO, Lokhit Pashu-Palak Sansthan. They experimented with camel milk marketing, camel wool shawls, and camel poo paper to augment incomes from camels.

Köhler-Rollefson&rsquos love and concern for camels and the Raika shines in her easy style of story-telling, often slipping into Indian English idiom. This is a story of the author&rsquos work, the flux in Raika society, the lack of value accorded to pastoral economy, and lives of camels skilfully braided together.