- Destinations

- Experiences

- Stay

- What's new

- Editor’s Picks

- Responsible Tourism

- CampaignsCampaigns

- Subscribe

Vision is the most blessed of the senses at the Kumbh Mela. Not long after you arrive at the fair, a ceaseless blare of lost-and-found announcements on the tannoys benumbs your ears. A smelly mix of drying urine and log-fire overwhelms your nostrils. A few days of street food makes a leathery toast of your tongue. A few weeks of jostling amid the world&rsquos largest crowd tends to leave a colourful mark or two on your skin. And yet, you do not want to close your eyes.

Why would you Imagine a city of thousands of tents that hunkers down temporarily on the sand between two storied rivers. In this city millions of people&mdashnaked and clothed, godly and ungodly&mdashbustle around in search of absolution or money, or both. Into this colourful mix, add the urgency of everyone having to take the holy dip of absolution on ordained days&mdashall within a few hours, all along a sandy stretch of just a few hundred metres. And you realise why the Kumbh is a wet dream for photographers.

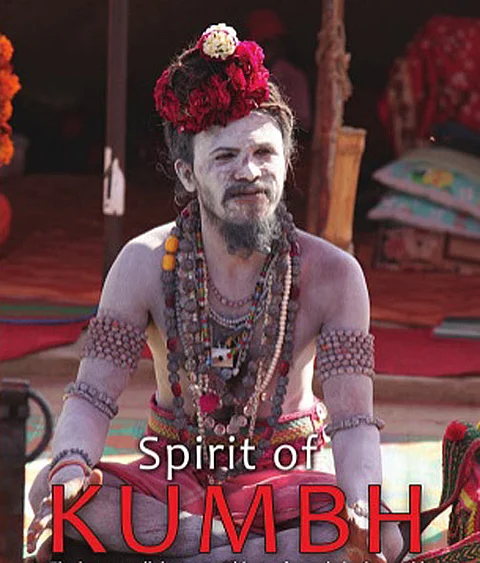

Perhaps Santosh Misra, an engineer turned IAS officer, had the dream, too. He has spent a number of years clicking away at the largest of the four Kumbhs, at Allahabad. A selection of those images has been made into the latest coffee-tabler on the topic. (Apart from the hundreds of images by Misra, the book features 19 clicked by Amit Kilam of Indian Ocean.)

In style, there&rsquos little that links the images in content, there&rsquos little that lifts them above the millions of other images of the Kumbh. The text, even when it steps out of Wiki-history, rarely complements the images. So we have Ram Puri, an American Naga sadhu, being colourfully pitched as &lsquothe Beverly Hills Baba&rsquo, but Annapurna Puri, who has a number of European followers, is dismissed as one with &lsquoan Anglo-Indian devotee&rsquo. There&rsquos only one thing that offers a tenuous connection among the pictures&mdashthe Ganga. Its rippled reflection in every other picture is the only thing that tells the reader, &lsquoThis too can flow.&rsquo