- Destinations

- Experiences

- Stay

- What's new

- Editor’s Picks

- Responsible Tourism

- CampaignsCampaigns

- Subscribe

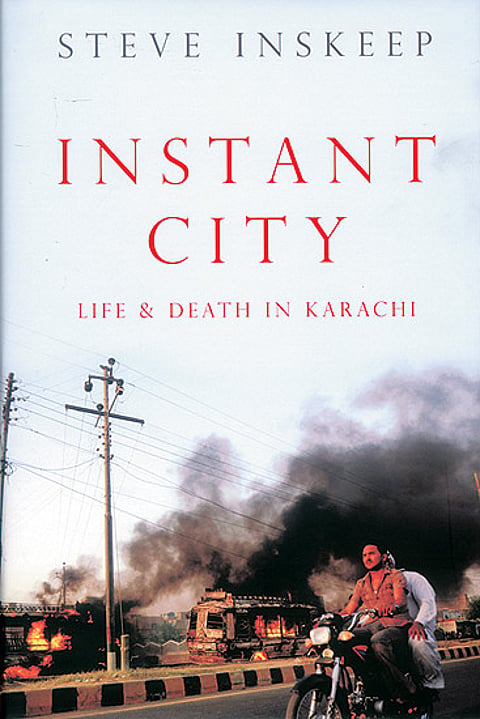

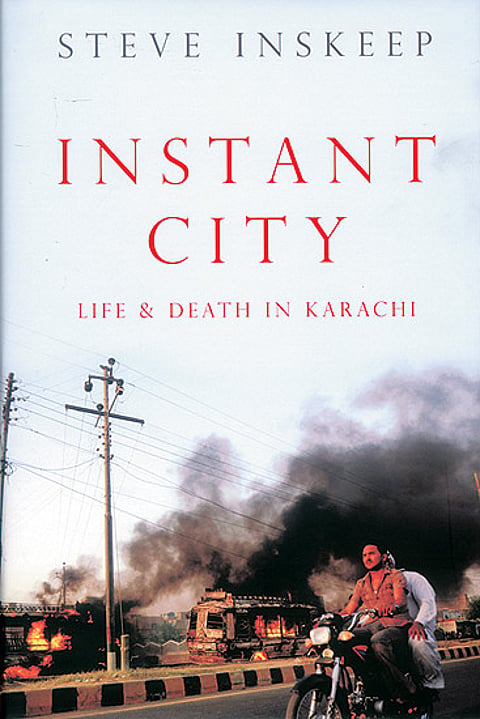

All cities are mad, they say, but the madness is gallant. All cities are beautiful, but this beauty is grim. In the city of Karachi, the protagonist of Steve Inskeep&rsquos Instant City Life & Death in Karachi, the beauty, and especially the madness, often originate from people finding themselves ever so often &ldquoon the wrong side of the dividing lines&rdquo. The book, then, in some ways can be read as a testimony to the agonising struggle over the soul of the city, and a sense of belonging, amongst Karachi&rsquos residents across the ages.

The two emblematic moments of this struggle are Partition and General Ayub Khan&rsquos coup. They are also emblematic moments in the age of what Inskeep calls &lsquothe instant city&rsquo.

&ldquoThe Partition of India could look so clean on a map,&rdquo Inskeep writes. &ldquoMuslims over here, Hindus over there, borderlines in between. It was never that simple.&rdquo For Inskeep, Partition marks one of the grand moments in Karachi&rsquos instantaneous transformation. Nearly 51 per cent of the city was Hindu when the cataclysmic event of Partition tilted the earth on which millions of Indians stood and &ldquoMuslims began tumbling downward into Karachi&rsquos reluctant embrace&rdquo.

The influx of vast numbers of Muslims as refugees and Mohammad Ali Jinnah&rsquos inability to stake out a position for the Hindus &mdash &ldquoHow could he propose unity as he led Muslims into a division so profound&rdquo Inskeep asks &mdash left the minorities stunned survivors, abandoned subjects, forced migrants. Here, the concept of instantaneity that Inskeep attaches to the spatial concept of the city becomes somewhat clear it was as if the moment of Partition changed Karachi overnight from the city &ldquowhere it was common for Hindus to pay homage at the shrines of Sufi saints and for Muslims to celebrate Hindu festivals&rdquo into the one marred today by the kind of divisions that culminate in attacks like the deadly December 2009 bombing of a Shia religious procession.

This Karachi disfigured by constant tensions and instabilities appeared as if &ldquoin a blink,&rdquo growing not only in the number of people it held but also in terms of their &ldquofrustrated dreams and unintended consequences.&rdquo

Other inadvertent changes to the fabric of Karachi occurred over ten years later with General Ayub Khan&rsquos attempt to move people out of central Karachi&rsquos informal neighbourhoods into rambling new suburbs with subsidised homes.

The chapter on the construction of one such settlement, Korangi, is an account of how urban development creates the debris of places and people cast outside the pale of value how such repositories of society&rsquos leftovers often take a turn for the unexpected, ending up exacerbating the very problems they had set out to correct.

In Karachi&rsquos case, illegal developments and slums crept up in the planned communities and many people were quickly forced to abandon them for want of adequate affordable housing and commuting options.

This kind of eviscerating urbanism, as Inskeep argues throughout the book, is central to the ways in which Karachi has changed. This is sometimes a source of jeopardy to urban life and economy, setting into motion a high-speed version of the process that has led so many ancient cities to ruin.

What will Karachi&rsquos fate be Inskeep&rsquos answer Karachi will decide for itself. Indeed, Partition and Ayub&rsquos coup are only two examples of the startling results of attempts, both deliberate and accidental, to refashion Karachi into something it&rsquos not. Inskeep&rsquos book is littered with many more such lightning rods of how grand dreams in some of the world&rsquos greatest cities are buried by simple entropy.

Through his thick description of Karachi, Inskeep not only unravels the constellations of social, institutional and religious histories of Pakistan itself, but also gently reminds us that Karachi shares this feature of schizophrenic growth &mdash its instantaneity &mdash with countless other anxious &ldquoinstant cities&rdquo in the developing world.