- Destinations

- Experiences

- Stay

- What's new

- Editor’s Picks

- Responsible Tourism

- CampaignsCampaigns

- Subscribe

&ldquoWelcome to Bihar,&rdquo says the student who wants to shake my hand as soon as the train rolls into Patna Junction, the modern incarnation of Pataliputra. &ldquoI hope you will come back again many times.&rdquo

I wouldn&rsquot know.

People persistently warned me before this trip Don&rsquot expect to come back alive from Bihar, they said.

Don&rsquot expect any roads or electricity, they went on gleefully. So, despite the hearty welcome by the student, who is on his way to his &ldquonative place&rdquo by the Nepali border, I am hesitant. I can&rsquot help but notice how the railway platform looks suspiciously similar to a freshly ploughed potato-field and I suddenly recall how Jug Suraiya famously said that the best time to come to Patna would have been in the days of the Buddha.

I do my best to follow Suraiya&rsquos advice and to travel back in time. The head attraction at the museum on Buddha Road is a life-sized statue of a well-developed woman known as the Didarganj Yakshi, dating from ancient times. The museum collection also has statues of the Buddha himself &mdash he was so respected here that one of the 64 gates in the city wall was named after him. Perhaps he even strolled down Buddha Road, maybe he met and preached to the voluptuous model.

If the Buddha has any relatives alive, it is reasonable to assume that they live in present-day Patna. I scan the faces of museum guards and ticket-sellers, for some characteristics of my imaginary Buddha. I readily admit that I want to get a sense of contact, however minuscule I wish to walk in his footsteps or see something that he may have looked at.

Must fight my vanity. Nirvana is the target.

The driver&rsquos name is Lal Dev, which interestingly means &lsquoDear God&rsquo. Like most gods he is something of a riddle He rarely speaks, but often shoots off an otherworldly grin.

The road is an endless row of potholes.

Dear God has an assistant, who waves joss sticks before the dashboard altar and, at regular intervals, steps out to ask for directions.

Usually there&rsquos some antique uncle sitting out there, keeping an eye on the crossroads through dusty spectacles, almost as if he were waiting for us.

This was the road the Buddha followed to Rajgir, where an enthusiastic maharaja offered the peripatetic monk half of his kingdom. That&rsquos the kind of stuff maharajas did in those days. However, the Buddha wouldn&rsquot let material circumstances tie him down to any one place. Yet he was to return here frequently, and his son Rahula grew up in a monastery nearby, in Nalanda, which developed into the world&rsquos greatest Buddhist university. Now, of course, it has closed down.

&ldquoWhat&rsquos that&rdquo asks one visitor staring quizzically at a ruin.

&ldquoThat&rsquos a stupa. A kind of temple,&rdquo replies the guard overseeing a huge mound of darkened tiles. The low afternoon shadow of the stupa falls across the fields.

&ldquoAchcha, a temple So where does one enter&rdquo

&ldquoYou don&rsquot,&rdquo the guard says.

&ldquoThen how is it a temple&rdquo

Good point, I think, because the discussion reinforces Buddhism&rsquos differences from other religions. But wherever it spread, stupas were built to hold relics of Buddhist teachers. The Nalanda stupa contains the Buddha&rsquos secretary&rsquos remains &mdash he had, among other things, been entrusted with tutoring the Buddha&rsquos son.

The guide claims there were 200 monasteries around the stupa, although only 11 have been unearthed. The main halls have platforms for the lecturer and there were 30 student chambers per floor. Some monasteries were nine storeys high, according to the guide, which reminds me of my cramped life as a student in Sweden. I can&rsquot help thinking that when Nalanda reached its zenith, it would still take a thousand years before Uppsala University was founded.

Meanwhile, people travelled from as far away as Korea and Sumatra to Nalanda, which boasted of some 1,500 teachers and 10,000 students. Eight out of 10 applicants were turned back after failing the admissions test. &ldquoThose who cannot discuss the finer points of Tripitaka are little esteemed and must hide in shame,&rdquo the Chinese Xuanzang noted after studying here in the seventh century.

&lsquoThe King&rsquos House&rsquo, Raja Griha, lies 10 kilometres to the south. Today it is a small bazaar surrounded by hundreds of camels leisurely chewing on twigs. In the Buddha&rsquos time the population is said to have been around 180 million. A Bihari gentleman tells me, &ldquoNo matter what figure we name, you must always divide it by six, because we Biharis like to exaggerate and where other people double their claims, we usually multiply by six.&rdquo I find the formula useful for estimating the kingdom&rsquos actual population 30 million may be quite accurate.

The Buddha used to live on a hill known as Vulture Peak. In those days philosophers were expected to renounce all possessions and never settle down &mdash it was a culture on the move, a lifestyle free from the shackles of society, a bit like the hippies of the 1960s. In the monsoon when travel became difficult, the solution was to find a cave &mdash cheap maintenance, no rent &mdash and for three months you philosophised there and prepared for the next tour. That&rsquos how the first monasteries came into being. Interestingly, the name Bihar is derived from the old word for monastery, vihara.

After much climbing I stumble into the cave beneath the peak. Pilgrims have decorated the entrance with prayer flags, but the cave itself is a low pit barely two metres deep, and I hit my head on the ceiling, sure that Buddha, too, bruised his bald skull here. A flat rock, which must have been the Buddha&rsquos bed-cum-sofa, is now an altar. Usually at Buddhist sites, the sights are from centuries after the Buddha&rsquos death and I suddenly realise that this is the only place that&rsquos not changed substantially since he was here.

It&rsquos a rare experience to sit at the mouth of the cave and meditate. So this is how he lived.

His birthplace Lumbini, in the lowlands of Nepal, is just across the border from India and in the first town on the other side I check into the downmarket Nepal Guesthouse, and chill out on the rooftop. It&rsquos swarming with backpackers on the way to Kathmandu, none of whom seem very interested in the fact that Buddha was born practically next door.

The following morning I borrow a bicycle to go the 30 kilometres to Lumbini. A memorial column from 249 BCE and the tank where the new-born Buddha got his first bath were discovered here by a German archaeologist a hundred years ago.

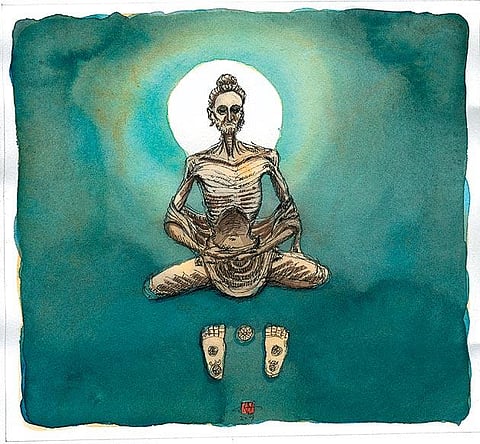

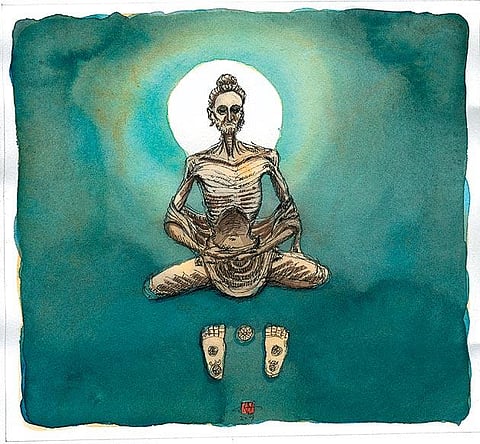

Buddha&rsquos father was the chairman of the municipal council in a city-state, either in Piprahwa in India or Tilaura Kot in Nepal &mdash nobody is really sure. According to a Pali text, one day the Buddha said, &ldquoSuppose I shaved off my hair and beard, put on the yellow robe, and went forth from the house-life into homelessness&rdquo Off he went, meeting gurus and ascetics, debating with seekers, and after six years he reached &mdash alone and dejected &mdash a village with an inviting fig tree (Ficus religiosa), a species later to be known as the bodhi-tree. Here he decided to wait for an answer &mdash or die.

The horse looks like it might keel over and die any moment. The driver lashes him. The horse meditates for a while &mdash and decides to oblige. Since the buses are very crowded, with passengers on the roofs, I go with this tongawallah. Like a true Bihari he exaggerated as he hustled me, &ldquoCome, I&rsquoll take you &lsquoBuddha Gaya&rsquo by Indian helicopter.&rdquo

Ignoring my protests he stuffs me into the back, on top of the luggage and some other passengers. Although the Buddha mostly walked, he may have travelled by horse, and so the tonga becomes my time machine. Here and there I glimpse monks, easy to spot from afar their skulls gleaming in the sun, their robes bright red and yellow.

Bodhgaya used to be pretty much off the tourist track until 1811 when a British survey team were told vague stories of Burmese worshippers who would come here, but of course they had no idea who the Buddha &mdash by then largely forgotten in India &mdash might be. The decorative curls on the statues led the colonialists to assume that the Buddha was some prehistoric African god, who for unknown reasons had spawned a cult following in Bihar.

Today, however, the village has a very cosmopolitan feel to it &mdash a reflection of the international appeal of Buddhism Tibetan, Bhutanese, Thai and Burmese monasteries, Chinese, Taiwanese and Vietnamese temples, a Japanese Buddha-colossus, a British meditation centre and German apfelstrudel in the coffee shops.

On a piece of rock I find a carving of the Buddha&rsquos footprints. For long he was depicted only through symbols (footprints, an umbrella, a throne, an empty saddle) &mdash suggesting that he had reached nirvana. So that is why we will never know what he actually looked like. Though he appears to have worn shoe-size 68.

After his enlightenment, the Buddha wandered to Rishipatana, a popular recreational area near Varanasi frequented by itinerant seekers, and preached his first sermon, setting the wheel of Dharma in motion. The best part was that everybody could get to know the meaning of life irrespective of caste or social status.

The road from Varanasi is flanked by the spillage of a bursting metropolis and mechanical workshops servicing the Grand Trunk Road. After a long ride we halt next to a gigantic stupa. There&rsquos also a park with fenced-in deer being fed ice cream wrappers by snickering children &mdash karmic misfits if ever there were any &mdash and a café with bright soda ads. While I refresh myself, I go through the Buddha&rsquos lectures and find that many contain miraculous displays.

I get a strange feeling that I could be reading Harry Potter He multiplied himself, turned invisible, walked on water, read minds and planted seeds that instantly grew into mango trees. The tricks would rope in curious onlookers, and are not as miraculous as they seem. To multiply was simple since all monks wore standardised robes &mdash there was no dearth of doubles. By this the Buddha cleverly demonstrated the rapid spread of Buddhism. The mango tree trick also symbolises the growth of Buddhism, and is performed by roadside conjurers even today.

As befits a true traveller, he died on tour. During a stay in Vaishali he ate some mean pork curry and suffered severe food poisoning. Despite this he walked all the way to Kushinagar &mdash in those days a somewhat insignificant cluster of mud huts, according to the old scriptures &mdash where he asked his followers to make a bed between two trees, the location of which was found during excavations in 1861-62. Then he spoke his famous last words, &ldquoIt is in the nature of all forms to dissolve, but you can attain perfection through perseverance.&rdquo

After the cremation, relics were brought back to Vaishali. Before I go in search for the Buddha&rsquos tomb, I have a non-veg meal in a seedy Patna restaurant and awake in horror at 4am, making a desperate dash for the loo. During my travels I&rsquove suffered as many forms of tourist diarrhoea as the Eskimos have words for snow &lsquothe Delhi-Belly&rsquo, &lsquothe Kathmandu Killer-Craps&rsquo, &lsquothe Farts of the Fakirs&rsquo, &lsquothe Calcutta Chromosome&rsquo, to name a few. This evil &lsquoPatna Poop&rsquo gives off a howling wind fierce enough to blow the bathroom door off its hinges.

Existence is dukkha, suffering (all due to trishna, craving), at least on a day like this when I have to rely on public transport, and I fully identify with the Buddha&rsquos death-throes. The bus driver in his camouflage cap looks like Fidel Castro without a cigar. &ldquoRocka-rocka,&rdquo says Fidel and plays a video featuring gyrating Bollywood aunties. The bus shakes and shudders, its passengers mesmerised by the TV set. After half a day, three bus changes, and an hour of walking, I reach Vaishali, basically just 70 kilometres north of Patna. In those days it was one of the world&rsquos first democratic states and a place the Buddha liked a lot, which is, perhaps, why his relics were buried here.

The fields are yellowish. The houses of yellowed mud. The shops are of dry bamboo and sun-bleached palm leaves. The hotel, government-run, has no running water, no electricity I&rsquom given a lantern and told to use the hand-pump in the yard.

The walk to where the Buddha gave his last major lectures, takes me past grazing buffaloes and goats, people harvesting, threshing, or just lazing around.

Out of nowhere a pot-bellied man in safari suit joins me. Not another loud tourist guide, I sigh. Strangely, he doesn&rsquot speak. He shows me silently around the excavation.

Archaeologists have found town walls, monasteries, coins and seals around here. Later, when I expect him to demand money, he leads me to his motorbike. I vaguely think, as we turn off the main road, that he might be one of those dacoits, plotting to chop off my head. But instead he drives me to Buddha&rsquos tomb in the jungle, a place I wouldn&rsquot have found without him. The burial stupa has a base of clay and measures seven metres, inside of which the remains were found in 1958.

The mysterious biker drives me back to my hotel and says that some relative of his works there. Then he&rsquos gone. I retire for the night, the sky over Vaishali starry and bright as skies only get in places with permanent power cuts. I drink Old Monk from a bottle I&rsquove carried, and spot a lantern in the distance. A boy comes with a tray of hot chapattis, potato curry.

In the midst of clichéd squalor, dukkha beyond remedy, Bihar is graceful with its old-fashioned kind-heartedness and hospitality. Probably the Buddha was treated the same way probably that&rsquos why he didn&rsquot bother to travel very far from Bihar.

At dawn I take my bath at the hand-pump. The water is warmer than the winter air. The sun disperses mist from the fields it&rsquos a beautiful day. Afterwards, when I&rsquom ready to leave for Patna, there&rsquos no trace of a bus. While I&rsquom brooding, one of those typical antique uncles sitting by the road nods at a white Ambassador. He says, &ldquoPatna.&rdquo

The driver opens the door without a word. After a few kilometres he picks up a man. Further down the road yet another. Still without speaking. The uncles get off at different places. An hour later we reach Patna and I&rsquom dropped in front of the railway station. No explanations are given, none needed. If I wasn&rsquot standing here on the rough earth that serves as a Patnese sidewalk, I would believe that the entire trip was a dream.I feel that the Buddha is watching. And pulling my leg.