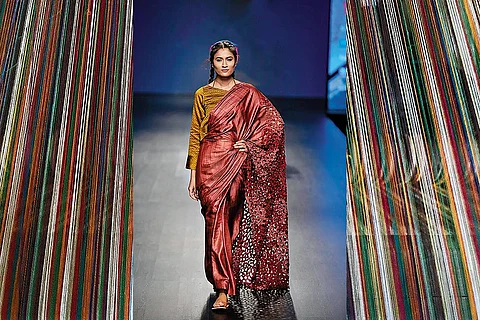

The Lure Of Lustre: How Chanderi Weavers Are Keeping Indian Fashion Alive With Modern Touches

The lore of the lustrous Chanderi sari has been woven intricately over time, with its roots spanning centuries, from mentions in Vedic scriptures like the Mahabharata to its royal revival. In 1910, a gold thread motif was added to the cotton muslin saris under the patronage of Madho Rao Scindia, the Maharaja of the erstwhile princely state of Gwalior. This golden thread that the world knows as zari not only accentuated the beauty of the saris but transformed them into luxury wearables.

An authentic handwoven Chanderi sari, known widely for its gauzy texture, has another significant tell: the motifs.

When I travelled to Chanderi, the textile town in Madhya Pradesh where these GI-tagged saris are made, a small-scale weaver named Bhagwan Das explained how the unique motifs or butas define an original Chanderi masterpiece.

"The Chanderi motifs can't be copied on a power loom," said textile revivalist Jaya Jaitly. "Chanderi weavers are content with their handlooms because technology can't replicate the labyrinthine details of a handwoven piece." Designer Vaishali Shadangule who has worked extensively with Chanderi reiterated what Jaitly said. "These meticulously woven designs bring life to the fabric and signify slow fashion."

The Yarn

We may identify the Chanderi region with its silk, but the area has a history of various weaves dating back to colonial times. The weavers initially spun khadi yarn by hand, but the Industrial Revolution acquainted them with an alternative in Japanese silk around the 1930s. These inexpensive, gossamer-thin yarns prompted the artisans to replace the cotton warps with silk and weave their first silk saris.

Post-Independence, the Chanderi weavers' cluster further restored the sheen of the fabric by integrating a silk warp with a cotton weft to present the world with "Chanderi cotton silk," a combination of silk and cotton fabric crafted using multiple-weft shuttles.

"From Chanderi cotton, pure silk to now cotton silk drapes, we make saris and other garments using these three yarns," said Das.

Reimagining Motifs

While few small-scale weavers like Rana Khan believe that the authentic beauty lies in the handwoven designs inspired by flora, fauna and celestial bodies, Chanderi's weavers are open to exploring new motifs and contemporary designs like geometric patterns. They incorporate these in Indo-Western fusion ensembles, co-ords, and home décor. Such modern patterns are often a result of encouragement from designers like Shadangule.

"We try to blend traditional styles like Chanderi floral art with trendy patterns like linear gradients, ensuring a mix of sustainability and what's in vogue," she said.

Likewise, Pratima Pandey's fashion label Pramaa revives the old butas with fresh structures and bright colours. "We figure out old motifs created by the forefathers of traditional weavers and meld them in our apparel, ensuring they resonate with contemporary needs."

Woven Air

Master weaver Mohammad Anwar tells me how the fabric is often called "woven air," a testament to its feather-light weight and lustre. "The beauty lies in its sheerness," he says, "which is achieved through degumming." This procedure is done before the fabric is dyed to prevent thread breakage during weaving.

Anwar explained the degumming process to me as he demonstrated his weaving skills using tana (warp mechanism), ruchch (wooden frames), jacquard (dobby/design plate), charkha (wheel to weft threads) and dyeing apparatus.

With cotton, silk and zari, these weavers create saris that range from INR 2,000 to INR 2 lakh. But the question is whether they are compensated enough. Their living conditions said otherwise as they told me about their inability to make ends meet during off-season. Financial security, job opportunities and pension for old age would go a long way in making the lives of the weavers better.